This book review was originally published in the Baltimore City Paper on May 11, 1994.

This book review was originally published in the Baltimore City Paper on May 11, 1994.

In Jay McInerney’s underrated 1985 novel Ransom, Christopher Ransom flees from the materialistic excess of life in Hollywood to search for moral purity in the city of Kyoto, Japan. He abandons his drug and drinking habits, he tries to remain celibate, he studies karate from a real Japanese sensei. But America keeps creeping back into his consciousness, tainting all his efforts with capitalist fever and the Protestant work ethic.

I felt a little bit like Christopher Ransom when reading Dance Dance Dance and Sixty-Nine, two novels by what Kodansha International proclaim to be “the best-selling young writers in Japan.” I wanted un-American books about un-American problems, only to discover that the primary concern of Japanese literary hotshots Haruki and Ryu Murakami (no relation) is America. Not necessarily America the chunk of land across the Pacific Ocean, but America the cultural influence, America the trendsetter, America the quiet infiltrator of the East.

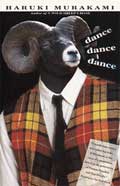

At first glance, Haruki Murakami’s Dance Dance Dance (a sequel of sorts to his previous A Wild Sheep Chase), far and away the better novel of the two, seems to have little to do with the land of Big Macs and rock n’ roll. The author’s skillful blend of murder mystery, spiritual quest, and the supernatural takes place mostly in Japan. But the currents behind the scenes hold deep resentment for the American cultural invasion that has left Japan a hollow, faceless player in the corporate mind games of the Western power structure.

At the beginning of Dance Dance Dance, the nameless narrator is a recently divorced freelance writer in search of some larger connection to society. He inhabits a Japan where individuals are no longer important, where “advanced capitalism” and the movement of yen between large corporations consume the public interest. After receiving a dream message from a former lover, however, the narrator suddenly finds himself entangled in connections to several individuals without knowing why: a clairvoyant 13-year-old girl, a big screen movie star and former junior high classmate, a one-armed chef, and a hotel receptionist.

Uncertain of how to weed through this confusion of characters and find once again his ex-lover Kiki, the narrator comes into contact with a strange entity from another world, cryptically named the Sheep Man. His advice to the narrator is, “You gotta dance. As long as the music plays…. Don’t even think why.” So the narrator learns to treat life in modern-day Japan as a dance, a meaningless jig between alienation and corporate money and murder, simply trying to balance the elements and make it through intact to the next day.

In Murakami’s novel, the intangible America haunts modern-day Japan like a ghost, seeping through stereo speakers and TV tubes and glaring on the pages of magazines. The mysticism of the East that’s for so long been associated with Japan has all but vanished into the “other world” of the Sheep Man; the narrator’s Japan is a land of Dunkin’ Donuts, flashy cars, and classic rock playing on the radio.

Ryu Murakami’s novel Sixty-Nine also deals with Western cultural invasion, but his attitude is the polar opposite of Haruki Murakami’s. Ryu’s slight roman a clef about his high school days delves into the Japanese youth rebellion of the late ’60s, a time of reaction against Western imperialism in Vietnam. The author’s conclusion about those momentous days, however, is that rebellion was simply a prank, a childish scheme to attract women’s attention.Murakami describes a Japan divided by marijuana brownies and Vietnam protests acted to the beat of The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Janis Joplin. But in the out-of-the-way, law-abiding town of Sasebo, narrator Kensuke Yazaki’s plan for liberation through a multimedia youth festival proves too much for the authorities to tolerate. The whole plot is depressingly similar to the Kevin Bacon teen flick Footloose.

Ryu Murakami’s novel Sixty-Nine also deals with Western cultural invasion, but his attitude is the polar opposite of Haruki Murakami’s. Ryu’s slight roman a clef about his high school days delves into the Japanese youth rebellion of the late ’60s, a time of reaction against Western imperialism in Vietnam. The author’s conclusion about those momentous days, however, is that rebellion was simply a prank, a childish scheme to attract women’s attention.Murakami describes a Japan divided by marijuana brownies and Vietnam protests acted to the beat of The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Janis Joplin. But in the out-of-the-way, law-abiding town of Sasebo, narrator Kensuke Yazaki’s plan for liberation through a multimedia youth festival proves too much for the authorities to tolerate. The whole plot is depressingly similar to the Kevin Bacon teen flick Footloose.

Yet whatever anti-authoritarian anger Sixty-Nine conjures up becomes an instant target for Murakami’s cynicism. Yazaki immediately counters his revolutionary mantras against the “capitalist lackeys” with an aside to the reader about how he never really believed in any of it, it was just something he read in a magazine once that sounded impressive.

Unfortunately, Murakami displays no sensitivity for the real politics that infused the period. Yazaki’s rural town of Sasebo could very well be that mid-western hick town from Footloose, with its stone-faced repressive authority figures and its clean-cut youth trapped in the cookie cutter system of societal placement.

But it’s Yazaki and friends who are the fools in Sixty-Nine, their rebelliousness depicted as mere anarchy and laziness.