This past week, I had the privilege of reading my short story “Mathralon” at the U.S. Library of Congress, as part of the “What If… Science Fiction & Fantasy Forum” run by the fabulous Colleen Cahill. Alas, my plans to videotape the event and stick it up on YouTube fell through, but those who are curious can look at some photos on my Flickr account. (Okay, so they’re not professional quality photos, and they give you the impression that there were only three people there. But they were taken by my mother-in-law, so you shut up about it.)

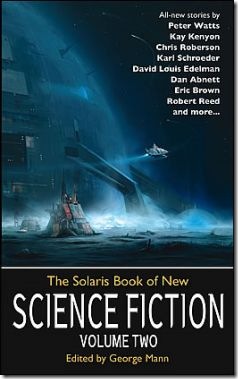

“Mathralon” is featured in The Solaris Book of New Science Fiction, Volume Two, edited by George Mann. (Here it is on Amazon.) The book is pipin’ hot off the griddle, and also features stories by Michael Moorcock, Peter Watts, Karl Schroeder, Mary Robinette Kowal, Chris Roberson, Kay Kenyon, Neal Asher, Paul Di Filippo, Eric Brown, Brenda Cooper, Dan Abnett, Dominic Green, and Robert Reed.

“Mathralon” is featured in The Solaris Book of New Science Fiction, Volume Two, edited by George Mann. (Here it is on Amazon.) The book is pipin’ hot off the griddle, and also features stories by Michael Moorcock, Peter Watts, Karl Schroeder, Mary Robinette Kowal, Chris Roberson, Kay Kenyon, Neal Asher, Paul Di Filippo, Eric Brown, Brenda Cooper, Dan Abnett, Dominic Green, and Robert Reed.

In the run-up to the book’s publication, I asked George if he would have a problem with me posting “Mathralon” on my website as a way to promote the book. He did not. And so I’ve posted “Mathralon” in full here on my website. I encourage you to share it with your friends, compose songs about it, act it out on YouTube videos — heck, if you like it enough, you might even go and buy an extra copy or two of the Solaris anthology.

Go read “Mathralon” here. But before you do, a few words about the story.

The first Amazon reviewer describes the story thusly: “This mostly reads like a type of manual. It tells how to mine a mineral, Mathralon. This is followed by a few pages about the isolated people who do the actual mining.” Well, yeah, I guess technically that’s accurate.

The story is told from a first-person plural point of view — kind of a Greek chorus sort of thing. It really has no plot, and there are no characters besides the nameless narrators and the nameless bureaucrats who oversee them.

Why did I write it this way? Because when I tried to write “Mathralon” with a more typical structure, it simply didn’t work. Originally the story was narrated by the head of a resistance movement of space miners who had just successfully rebelled against their oppressive robot overseers. The narrator went in to Howard Company headquarters to negotiate a settlement and slowly discovered what you’ll discover from reading the story. Meanwhile he’s got to navigate this building full of evil Terminator robots that were called I Don’t Remember And Who Really Cares Anyway.

And every time I read through what I had written, I had the same reaction: evil Terminator robots? Are you frickin’ kidding me? There are certainly authors out there who can pull something like that off, but I’m not one of them.

Eventually I came to the realization that I was trying to shoehorn a conventional action plot into this shiny leather shoe of an idea about a planet of space miners. I realized that the idea was the interesting part, and this whole business about the resistance and the evil Terminator robots was just my half-assed attempt to make it Exciting and Thrill-Packed. When I stripped away all of the extraneous stuff — plot, character, dialogue, etc. — the whole thing just grooved.

So what was this idea I got so excited about?

I believe it started with a friend of mine who writes mathematical models for automated stock trading. There’s no human being there reading the Wall Street Journal and making informed decisions about what to buy and sell on any particular day; it’s just a computer program making these decisions based on past performance and current market conditions and the arrangements of chicken entrails and who knows what else. Thinking about this, I wondered: what if all the entities on the other end of these transactions were automated computer programs too? Hell, what if the actual companies represented by these stocks were run by automated computer programs?

Take this out to loony, science fiction extremes and you start to reach some very interesting philosophical territory. You could have automated General Motors factories building cars, based on specs determined by automated computer programs that study market trends. They glean those market trends by reading publications that are also generated by automated computer programs, based on purchases by companies who are also run by automated computer programs, and so forth and so on.

Take this out to loony, science fiction extremes and you start to reach some very interesting philosophical territory. You could have automated General Motors factories building cars, based on specs determined by automated computer programs that study market trends. They glean those market trends by reading publications that are also generated by automated computer programs, based on purchases by companies who are also run by automated computer programs, and so forth and so on.

What if over thousands of years you built an automated economy that functioned so well that it outlasted the people who built it? Eventually you would get to the point where the remaining human cogs are servicing a machine that’s become more important than the thing the machine was built for.

Of course, this kind of thing is hardly virgin territory in science fiction. You’ve got your hackneyed Matrix and Terminator scenarios here — our machines are coming allllliiiiiiiiive and turning eeeevil! There’s also the famous Ray Bradbury story from The Martian Chronicles, “There Will Come Soft Rains,” which made a really big impression on me when I read it in junior high school. But even though I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Bradbury here, I was really after something different.

You hear a lot of talk about “keeping the economy going,” as if the economy was just a big machine we’ve built that’s taking us somewhere. But the interesting thing to me is the fact that the economy doesn’t even exist. In fact, most of these things that are so important to us — money, country, job, relationships — they don’t actually exist either. Try looking around for the United States of America sometime. You won’t find it, because it’s really just a shared delusion. You’ll find people, you’ll find land, you’ll find buildings, but you won’t find a United States of America. Countries, like money, like economics, like marriage, like careers, are simply virtual constructs we’ve created to make our lives easier.

John Lennon was right. If we all woke up tomorrow and imagined there were no countries, they simply wouldn’t exist anymore.

I’m not putting my lot in with the anarchists here, and I’m aware that I’m starting to drift off into late-night pot-fueled college philosophizing. Any minute I might tell you that the whole universe could just be an atom inside a giant’s finger — and there could be a whole universe inside YOUR finger too. So I’ll stop here. But I think every once in a while it’s a good idea to remind ourselves that you don’t owe these virtual constructs anything. They’re here to service us, not the other way around. We tend to forget that.

That’s the germ of the idea behind “Mathralon.” Read, enjoy, and discuss in the comments below, if you’re so inclined.