Since I’m thinking about the late, great Kurt Vonnegut, I decided to do a short summary of his works here, along with my take on them and my star ranking of each. Vonnegut graded his own books in the course of his collection Palm Sunday, and I’ve included those rankings here too. Keep in mind that it’s been many years since I’ve read some of these books, so my remembrances of a few might be a bit off.

Player Piano (1952) — 3 1/2 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: B)

A relatively straightforward satire of a dystopian future about mechanization and its effects on blue-collar workers a la Huxley’s Brave New World. Vonnegut was still finding his voice here, so you’ll find relatively little of his trademark humor or authorial noodling. Some of the symbolism is a bit clunky and obvious. Yet his deep and abiding humanism still shines through every page.

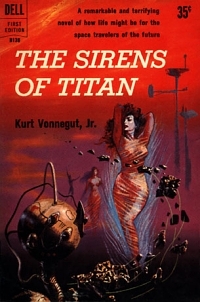

The Sirens of Titan (1959) — 4 1/2 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A)

The Sirens of Titan (1959) — 4 1/2 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A)

The classic space-faring science fiction story as written by Salvador Dali and Lenny Bruce after smoking lots of weed. Vonnegut comes out after a seven-year hiatus swinging with a fully developed voice. The cosmic speculation here about the purpose(lessness) of human existence is both cynical and mindblowing.

Mother Night (1961) — 5 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A)

An angry and morally biting story about a Nazi turncoat on death row in Israel post-World War II. This is perhaps the most conventional of all Vonnegut’s novels, and one of his most heartbreaking. The moral, as spelled out in the author’s own preface: “We are who we pretend to be, so we must be careful who we pretend to be.” Don’t miss the Nick Nolte film adaptation either.

Canary in a Cathouse (1961) — See Welcome to the Monkey House below.

Cat’s Cradle (1963) — 5 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A+)

The novel pits the cold and brutal scientific worldview of Dr. Felix Hoenikker against the ludicrous made-up religion of Bokononism. The adherents of Bokononism engage in silly rituals, speak gibberish to one another, hold contradictory beliefs about God, and have lots of sex. On a purely metaphysical level, the Bokononists are dead wrong about how the universe works; and yet Hoenikker’s scientific truths bring the world nothing but misery and apocalypse.

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965) — 4 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A)

Vonnegut’s ode to community and civic responsibility, and how they can go horribly awry. A comic American novel about an eccentric philanthropist and the lawyer who tries to bring about his downfall in the tradition of Sinclair Lewis. I believe this is the novel that introduces Vonnegut’s fictional alter ego Kilgore Trout.

Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) — 5 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A+)

Vonnegut writes about Billy Pilgrim, a World War II veteran and witness to the firebombing of Dresden (as Vonnegut himself was). Like the Bokononists, Billy’s defense against the horrors of the world is to retreat into insanity. He decides that he’s “come unstuck in time” and become the plaything of a fantastic race of aliens who experience their lives by dipping in and out of time at their leisure. The film adaptation is… eh.

Welcome to the Monkey House (1968) — 5 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: B-)

The seminal collection of KV short stories, repackaging almost all of the stories from Canary in a Cathouse and adding lots more. Includes classics such as “Harrison Bergeron,” “Report on the Barnhouse Effect,” and the title story. Alternately hysterical, wistful, psychedelic, and just plain groovy. Yes, there are a couple of clunkers here, but the magic shines through.

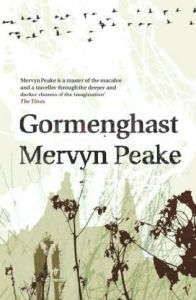

Gormenghast is a suitable companion-piece to Titus Groan. The two are so alike in tone and theme, that they seem to have been written in a single burst of inspiration. Peake provides us with an extended cast of characters, this time including Headmaster Bellgrove and his professors; he follows the rise of Steerpike’s crooked ambitions to their ruinous end; and he gives us a climactic manhunt that’s every bit as insanely drawn out as the battle between Flay and Swelter from the first novel.

Gormenghast is a suitable companion-piece to Titus Groan. The two are so alike in tone and theme, that they seem to have been written in a single burst of inspiration. Peake provides us with an extended cast of characters, this time including Headmaster Bellgrove and his professors; he follows the rise of Steerpike’s crooked ambitions to their ruinous end; and he gives us a climactic manhunt that’s every bit as insanely drawn out as the battle between Flay and Swelter from the first novel. I think I’ve discovered now why authors do that.

I think I’ve discovered now why authors do that.