Five guys hang around in a diner in Baltimore in 1959. One of them’s about to get married. All of them are restless, unsure which paths they’re going to take through life. They relive old times, smoke too much, and get into mischief as the new year approaches.

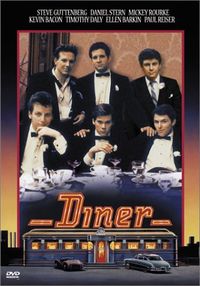

Doesn’t sound like much of a premise, but that’s the basic plot of Diner (1982), Barry Levinson’s first movie and one of the greatest coming-of-age stories ever put to film. It also happens to be one of my favorite films of all time, and (with the exception of The Empire Strikes Back) possibly the closest to my heart. (Read IMDB’s profile of Diner.)

Diner isn’t just a coming-of-age story for college-age boys; in many ways, it’s a coming-of-age story for America as well. The story takes place in the last days of 1959, a very symbolic time for the U.S. Fidel Castro has just recently taken power in Cuba and will soon align himself with the Kremlin — a fact that Levinson subtly reminds us of by having Eddie (Steve Guttenberg) and Elyse decide to honeymoon there. (Although whether a Cuban honeymoon would have still been possible in January of 1960 I don’t know.) In fact, all kinds of tumultuous events are right around the corner for these young men: the social revolution of the ’60s, racial integration, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Martin Luther King’s Dream, Vietnam, the assassination of the Kennedys. Not to mention the more prosaic crises of marriage, career, child rearing, adulthood, and responsibility.

Diner isn’t just a coming-of-age story for college-age boys; in many ways, it’s a coming-of-age story for America as well. The story takes place in the last days of 1959, a very symbolic time for the U.S. Fidel Castro has just recently taken power in Cuba and will soon align himself with the Kremlin — a fact that Levinson subtly reminds us of by having Eddie (Steve Guttenberg) and Elyse decide to honeymoon there. (Although whether a Cuban honeymoon would have still been possible in January of 1960 I don’t know.) In fact, all kinds of tumultuous events are right around the corner for these young men: the social revolution of the ’60s, racial integration, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Martin Luther King’s Dream, Vietnam, the assassination of the Kennedys. Not to mention the more prosaic crises of marriage, career, child rearing, adulthood, and responsibility.

So Diner represents a last hurrah for these young men. The last flush of innocence. Some of these boys might very well be lying dead in the jungles of Vietnam within a few years.

How do the Baltimore boys choose to fill their last days of innocence? By reliving their glory days of high school, of course. They shoot the shit at the Fells Point Diner until all hours of the morning; they pull pranks on one another; they shoot pool, go to the movies, watch TV, hang out at strip clubs. They cheer on friend Earl as he valiantly attempts to conquer the “whole left side of the menu” in one feat of gustatory bravado. They settle old scores and rehash old arguments. Eddie leaves the door open for bachelorhood by requiring his fiancee to pass a football quiz before he’ll marry her.

But despite their best attempts, they can’t stave off the coming of adulthood forever. Shrevie (Daniel Stern) already has a wife (Ellen Barkin) and a budding career as a television salesman. Billy (Timothy Daly) has gotten his childhood sweetheart (Kathryn Dowling) pregnant. Fenwick (Kevin Bacon)’s trust fund will be running out when he turns 23, forcing him to find some kind of path for himself. Boogie (Mickey Rourke) has gambled his way so far into debt that he’s forced to sign on with his father’s old friend Bagel (Michael Tucker) in the home improvement business. (A nice segue for Levinson’s next Baltimore film, Tin Men [1987], which centers on a pair of aluminum siding salesmen in the ’60s.)

(It’s worth noting that although Paul Reiser’s character Modell has a good amount of screen time and has been added onto the DVD box cover for marketing purposes, he’s not a significant player in the film. Modell has no real story arc to speak of, and his role in Diner is mainly that of comic relief. A role that he performs admirably, I might add.)

In some cases you can practically mark these boys’ transition to manhood on a scorecard. Witness the scene where Boogie tries to get Carol Heathrow (Colette Blonigan) to “go for his pecker” in a darkened movie theater. To the rest of the guys egging Boogie on, this is just a lark, something to laugh about later at the diner; but for Boogie, his future (and possibly his life) rests on pulling off enough crazy bets like this to pay off his massive gambling debt. As far as Boogie’s concerned, adolescence is over.

Likewise Fenwick’s Nativity scene desecration that lands him in jail overnight. When you’re a kid, getting hauled in by the cops for a bit of mischief is almost a badge of honor; but when you’re an adult, things change. How long until Dad shows up with the bail money? What kind of permanent black mark is going on Fenwick’s record for this little stunt? Can you imagine appearing at a job interview as a college drop-out with no appreciable skills, an alcohol problem, no money, and a big fat misdemeanor on your record?

Throughout the whole film, Levinson gives us pitch-perfect dialog, largely improvised by the then-neophyte cast members; understated camera work that stays out of the way, for the most part; and a loving (and seemingly accurate) recreation of Baltimore in the 1950s. There are also a number of fine brush strokes that go by almost unnoticed on the first viewing: the fact that you never see Elyse’s face; the jackhammer acting as soundtrack for the scene where Tank (John Aquino) roughs up Boogie on the street; the way the camera lingers on Eddie’s family’s black maid for a brief moment and the almost forced neutrality on her face.

The final scene, where Elyse tosses the bride’s bouquet into the audience, provides a nice tidy bit of symbolism. The bouquet lands on the table in front of the Diner guys, signaling that responsibility has finally arrived. It’s been staring them in the face for years; but now, suddenly, adulthood is here.

But is this a happy ending? It’s hard to say. Billy’s relationship with Barbara and the fate of their unborn child remain unresolved. Eddie’s headed for a one-sided marriage with a woman who will probably resent his pigheadedness. Shrevie and Beth have come to a nice temporary truce, but only time will tell if it’s merely a plateau. Fenwick is jobless, careerless, addicted to drink, and soon to face the loss of his trust fund. Boogie’s earned a reprieve from his gambling problem, but whether he can conquer his personal wanderlust and make a career under Bagel’s tutelage is unknown.

“We’ll always have the diner,” Shrevie assures Eddie during his hilariously bad pep talk about marriage. But those of us on the other side of thirty know that this statement simply isn’t true. Friends move on. Careers intervene. Life kicks you in strange and unexpected directions.

Diners close down.