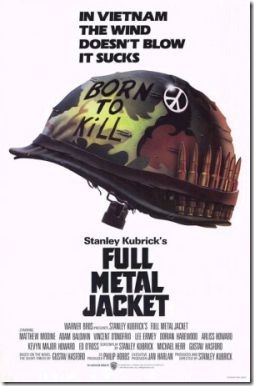

Nobody seems to be paying attention to the fact that 2007 marks the 20th anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Warner Home Video finally released a deluxe 2-DVD edition just last week, along with remastered editions of The Shining, 2001, A Clockwork Orange, and a few others.

Why is it a shame that nobody’s marking the occasion? Because Full Metal Jacket is one of the most meticulously crafted films of the past 20 years. I think it’s damn near perfect.

(Interesting side note: Believe it or not, this will be Full Metal Jacket‘s first home video release in widescreen. The film was originally shot in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, what you and I call “widescreen.” But if you’re an eccentric genius like Stanley Kubrick, you get to make unconventional decisions. Before his death Kubrick decided that, since 98% of the world’s TV sets back then had a 4:3 aspect ratio — i.e. “fullscreen” — henceforth and forevermore his films would be released in a 4:3 aspect ratio. None of that devil letterboxing for Stanley! It’s only now that Warner Home Video, with the collaboration of the Kubrick estate, is restoring the films to their original specs.)

(Interesting side note: Believe it or not, this will be Full Metal Jacket‘s first home video release in widescreen. The film was originally shot in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, what you and I call “widescreen.” But if you’re an eccentric genius like Stanley Kubrick, you get to make unconventional decisions. Before his death Kubrick decided that, since 98% of the world’s TV sets back then had a 4:3 aspect ratio — i.e. “fullscreen” — henceforth and forevermore his films would be released in a 4:3 aspect ratio. None of that devil letterboxing for Stanley! It’s only now that Warner Home Video, with the collaboration of the Kubrick estate, is restoring the films to their original specs.)

Audiences have had a peculiar relationship with Full Metal Jacket since its debut on July 26, 1987. It’s much loved in some quarters, but it’s equally despised in others. Everyone seems to appreciate the taut first act set in a Parris Island Marine boot camp, yet many never get over the film’s sudden shift to Vietnam in its second half. Even so perceptive a critic as Roger Ebert famously called the latter half of Full Metal Jacket “a series of self-contained set pieces, none of them quite satisfying.”

But Full Metal Jacket is designed to be a two-part story; just about everything you see in the first half of the film has a parallel in the second. It’s a structure Kubrick has used before (cf. the apes/the astronauts in 2001, and Alex’s life before/after his treatment in A Clockwork Orange).

More than that, the film is full of dualities: Joker’s helmet with the peace symbol and “Born to Kill” inscribed on the side (“I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man… The Jungian thing, sir”). The two dramatic deaths at the end of each section. The two-mindedness of the American public about the war. Joker’s own conflicting desires to “get into the shit” and to get out of there as quickly as possible. His dual nature as Leonard’s teacher and as the one who beats Leonard the hardest. And so on.

Of course, most of the moviegoing public doesn’t want to see films about Jungian dualities, and so people often go into Full Metal Jacket with false expectations. Hollywood generally only gives us three categories of war films: (1) the anti-war film (Platoon, Kubrick’s own Paths of Glory) (2) the war-is-sordid-but-necessary-and-sometimes-ennobling film (Saving Private Ryan), and (3) the out-and-out propaganda film (John Wayne’s The Green Berets, 300). But what do you do with a Vietnam movie that not only refuses to take a stand on the Vietnam War, but actually embraces its contradictions? “Do I think America belongs in Vietnam?” Crazy Earl says in response to a question from the television interviewers in FMJ. He looks totally perplexed, like he’s never even considered the question before. “I don’t know. I belong in Vietnam, I’ll tell you that.”

So if you’re going to get the most out of Full Metal Jacket, be prepared to take the long view. The way long view, the view of an alien civilization dispassionately studying humanity under a microscope. Like those hypothetical aliens, Kubrick rarely makes moral judgments; he simply observes. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, Joker, Animal Mother, the Vietnamese sniper, even the crazy gunner gleefully shooting down fleeing Vietnamese civilians from a moving helicopter — the film doesn’t really take anybody’s side. It doesn’t give you convenient moral labels to tell you who the good guys and who the bad guys are.

Take Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played with vicious brio by R. Lee Ermey (you know, the guy who’s played the military drill sergeant in every fucking movie since 1987). At first blush, he seems like as good a candidate as any for a villain in this movie. A manipulative brainwasher, a callous tool of the U.S. government. But on repeated viewings, you realize that he’s not the villain at all — quite the opposite. He’s doing his best to prepare these soldiers to survive out in the field. He’s a father figure. He’s a protector and teacher. He’s Obi-wan Kenobi, if Obi-wan Kenobi called his Padawan learners “unorganized grabastic pieces of amphibian shit.”

“Because I am hard you will not like me,” says Hartman. “But the more you hate me, the more you will learn.” Didn’t Mr. Miyagi say something similar to the Karate Kid when making him paint the fence?

Put in that light, Hartman’s abuse of Leonard Lawrence (Vincent D’onofrio) becomes not just understandable; it’s necessary. Look at the scene where the platoon goes tearing through the mud in slow motion, only to have Leonard trip and pull the whole team down into the mud with him. We fat and happy civilians look at that scene and think, why doesn’t someone give that poor kid a hand? Hartman looks at that scene, and he thinks: that kid’s not just going to die in Vietnam, he’s going to get a whole shitload of other Marines killed too.

So Hartman is playing the role of the Teacher. But you know what happens to the Teacher in all these stories: he dies. In fact, he must die, because our Hero must learn to prove himself, alone.

Who’s our hero in Full Metal Jacket? He’s called the Joker (Matthew Modine). His name is never given, but if you look closely, you can see that the nametag on his shirt says “J.T. Davis.” And Full Metal Jacket is the story of his coming of age, the story of his transformation from protected child to self-actualized soldier.

At the film’s outset, he’s a gentle soul who’s trying his best to maintain an ironic detachment from the reality of the Vietnam War. He responds to Hartman’s diatribes with a mock John Wayne swagger; his “war face” is the pathetic imitation scream of a man who’s only seen death on TV; he tells the television crews that he wants to be “the first kid on my block to get a confirmed kill.” For the Joker, war is something remote. Death is something that happens to other people at a distance.

At the film’s outset, he’s a gentle soul who’s trying his best to maintain an ironic detachment from the reality of the Vietnam War. He responds to Hartman’s diatribes with a mock John Wayne swagger; his “war face” is the pathetic imitation scream of a man who’s only seen death on TV; he tells the television crews that he wants to be “the first kid on my block to get a confirmed kill.” For the Joker, war is something remote. Death is something that happens to other people at a distance.

But over the course of the next 120 minutes, Joker will see the barriers between him and death slowly stripped away. Notice how the authority figures protecting Joker from the big, bad world become less and less authoritative as the film goes on. At first, we have the stern and menacing Gunnery Sergeant Hartman; then there’s the sour-faced colonel who tells Joker to “get your head and your ass wired together, or I will take a giant shit on you”; next there’s Lieutenant Touchdown, who seems competent if not particularly fearsome; then there’s Crazy Earl, who’s hardly much of an authority figure at all. By the time Cowboy takes command of the squad, you can see that he’s too green to have any sway over the anarchic Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin, now known to many as Jayne Cobb from Firefly). In the last scenes, even Cowboy is gone, leaving the Marines bereft of any real authority figure.

When we reach the last minutes of Full Metal Jacket, Joker comes face to face with death for the first time. As he faces down the Vietnamese sniper, we realize that Joker’s never really been under fire before. Nor has he ever killed another human being. Oh, he’s hunkered down in a bunker during the Tet Offensive and fired wildly at darkened figures in the distance. But to look the enemy directly in the eye and pull the trigger? No.

So Joker has reached his moment of truth, the moment that Gunnery Sergeant Hartman was trying to prepare him for. Can Joker set aside the irony, the sarcasm, the phoniness, and perform the job he signed up to perform as a Marine?

No. Joker fails, as Hartman foreshadowed way back in Parris Island. “Your rifle is only a tool,” he said. “It is the hard heart that kills. If your killer instincts are not clean and strong, you will hesitate at the moment of truth. You will not kill.” Joker hesitates, his rifle jams, and he withers under fire. He reaches for his pistol, drops it. Only by dumb luck — by the quick thinking of his buddy Rafterman, who Joker tried to leave behind — does he survive.

Earlier in the film, Joker asked the helicopter door gunner incredulously “How can you shoot women and children?” Now the question comes back to haunt him as Joker stands over an enemy sniper who is both a woman and a child (about 16, by the looks of her). The camera lingers over his face as he finally accepts the duality of man, the Jungian thing. Human beings are savage and civilized, kind and cruel, noble and deranged. Joker shoots.

Full Metal Jacket ends with Joker marching confidently alongside his brothers singing the Mickey Mouse Club theme song. “I am so happy that I am alive, in one piece and short,” Joker narrates in the end. “I’m in a world of shit… yes. But I am alive. And I am not afraid.”