An ordinary guy finds a suitcase full of thousand dollar bills. There’s no one around. Instead of going to the cops, the guy figures it’s his lucky day and takes the money. Which works just dandy until the big bad motherfuckers who own the suitcase decide to come looking for it.

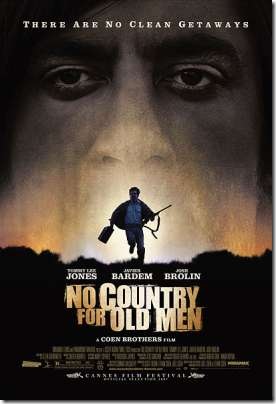

You’ve seen that film a thousand times before, and it’s essentially the plot of Joel and Ethan Coen’s brilliant new film, No Country for Old Men (based on the Cormac McCarthy novel of the same name). It’s one of the standard thriller plots that crawls out of Hollywood every five years dressed up in a slick suit of violence with a little flower of moral conundrum stuck to its lapel. The Coens have entertained a few variations on the suitcase-of-money scenario themselves (see Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and The Ladykillers).

You’ve seen that film a thousand times before, and it’s essentially the plot of Joel and Ethan Coen’s brilliant new film, No Country for Old Men (based on the Cormac McCarthy novel of the same name). It’s one of the standard thriller plots that crawls out of Hollywood every five years dressed up in a slick suit of violence with a little flower of moral conundrum stuck to its lapel. The Coens have entertained a few variations on the suitcase-of-money scenario themselves (see Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and The Ladykillers).

Here’s the thing. No Country for Old Men took that dandy little thriller behind the woodshed and beat its ass bloody.

That No Country for Old Men is fiercely entertaining is not really the point. Some audiences can’t see past the offbeat humor and treat the Coen Brothers’ films like hip Quentin Tarantino trifles. Critics often fail to see the point too. They’ve labeled the work of the Coens nihilistic, or misanthropic, or just plain vicious. They call the Coens’ films empty exercises in technical virtuosity without soul or subject.

These critics couldn’t be more wrong. Joel and Ethan Coen have an ongoing subject, and it’s a subject that they discuss intelligently and with compassion. Their subject? The American Dream.

You know, the American Dream: the idea that any penniless schlub born in a broken-down shack can, through grit and hard work, one day become Andrew Carnegie, or Sam Walton, or Bill Gates. It’s a free country! Opportunities unlimited! There’s supposed to be a proper moral framework propping up the whole thing, but somehow in the latter half of the twentieth century it became all about the money. Americans are obsessed with the stuff, whether in the affirmative sense (money enables you to follow your hopes and dreams) or in the negative sense (money can’t buy you happiness). Either way, material wealth always seems to be the fulcrum around which the whole American moral universe teeters. Rather appropriate when you think about it, considering that the United States was largely founded by a bunch of rich white landowners who were pissed off at the King of England because their taxes were too high.

Regardless, the American Dream is what it is, and for whatever reason Joel and Ethan Coen seem to have chosen it as their topic. In film after film, ever since 1984’s Blood Simple, the Coens have been steadily dissecting this Dream. Analyzing it, tearing it up, and stitching it back together. Charting out the ways it can corrupt us and demean us.

Witness Fargo, the story of a dumbass car salesman whose shame about his inability to provide a better life for his family leads him to fraud, extortion, and ultimately murder. Witness The Hudsucker Proxy, a cartoony take on Frank Capra in which a naive dimwit strives to reach the top of a major corporation only to find himself the puppet of his corporate masters. Or The Big Lebowski, featuring a ’60s reject with no ambition higher than getting his rug back, who is nonetheless sucked into the scheme of a corrupt self-styled philanthropist to steal a million dollars. Or The Man Who Wasn’t There, starring yet another dim bulb who’s thrust unprepared into a world of ambition by his wife’s philandering and is ultimately undone by it.

What do all the Coen protagonists have in common? They’re all ambitious schemers dissatisfied with the status quo, looking for unorthodox ways to achieve that American Dream.

And why not? You think the Carnegies, the Kennedys, and the Rockefellers got to their lofty positions by diligently punching the clock in a middle management job? You often hear the phrase these days that “well-behaved women rarely make the history books,” and it is, by and large, true. It’s certainly possible to earn a comfortable living on a middle-class salary with annual scheduled 5 percent raises. But to have Rockefeller money, or Perot money, or Gates money? The big American fortunes don’t come from middle-class salaries with 5 percent raises that are wisely invested. Some of them come from slave trading, bootlegging, war profiteering, and drug smuggling. Successful businessmen in this country often bribe law officials, extort politicians, oppress workers, and bully the competition.

And why not? You think the Carnegies, the Kennedys, and the Rockefellers got to their lofty positions by diligently punching the clock in a middle management job? You often hear the phrase these days that “well-behaved women rarely make the history books,” and it is, by and large, true. It’s certainly possible to earn a comfortable living on a middle-class salary with annual scheduled 5 percent raises. But to have Rockefeller money, or Perot money, or Gates money? The big American fortunes don’t come from middle-class salaries with 5 percent raises that are wisely invested. Some of them come from slave trading, bootlegging, war profiteering, and drug smuggling. Successful businessmen in this country often bribe law officials, extort politicians, oppress workers, and bully the competition.

The Coen Brothers protagonist sees a world that’s stacked against him. He’s stuck in a lower-middle-class rut with no upward mobility in sight. He’s not a venture capitalist or a bond trader or a software mogul. He’s (in chronological order by film) a bar manager, an ex-con factory worker, a middling Irish hood, a struggling screenwriter, a graduate of the Muncie College School of Business, a failing car salesman, an unemployed slacker, a convict sent up for practicing law without a license, a small-town barber, a high-powered attorney (okay, let’s just skip Intolerable Cruelty), and an itinerant con man.

With No Country for Old Men, Joel and Ethan Coen give us another one of these would-be Andrew Carnegies in the form of Llewelyn Moss, a welder and Vietnam veteran (in an astonishingly understated performance by Josh Brolin). Llewelyn stumbles on the aftermath of a drug deal gone wrong, finds a suitcase filled with two million dollars of drug money, and naturally assumes, in that uniquely American way, that he can “take on all comers” to keep it. He knows full well that there’s no pot of gold waiting for him after retirement from the welding trade; if he’s going to make a move up the ladder, if he’s going to follow the American Dream, Llewelyn has to jump into this with both feet.

Unfortunately, this opportunity leads him into the path of some unidentified cartel that’s willing to go to the mat to get back their cash. Towards that end, the cartel hires a lone assassin named Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem). Chigurh isn’t your typical hit man. He’s kind of like the Terminator, if the Terminator wasn’t such a sentimental, weak-kneed pussy. He’s like Hannibal Lecter’s evil twin. This dude is bad, and he walks around West Texas indiscriminately killing just about everyone he crosses with a big cattle gun.

You couldn’t think up a more classic American conflict than this. A laconic cowboy taking on an assassin hired by corrupt businessmen, in Texas no less. A fight against incredible odds. A good ol’ Southern boy raised with good manners against a Godless, thoughtless Mexican killing machine. Blue-collar worker up against the men with the big money.

You couldn’t think up a more classic American conflict than this. A laconic cowboy taking on an assassin hired by corrupt businessmen, in Texas no less. A fight against incredible odds. A good ol’ Southern boy raised with good manners against a Godless, thoughtless Mexican killing machine. Blue-collar worker up against the men with the big money.

Now, big spoiler here. So stop reading now if you don’t want to know how this ends.

Ready?

Llewelyn Moss loses. He loses badly, in fact — gunned down in a cheap El Paso motel, possibly without even getting a shot off himself. In this he follows in the tradition of Coen Brothers Protagonists like Fargo‘s Jerry Lundegard, who whines and thrashes like a baby as the police collar him; The Ladykillers’ G.H. Dorr, who persists in his elaborate heist to the death of him and all of his co-conspirators; Raising Arizona‘s H.I. McDonnough, who sheepishly owns up to his ineptitude and returns the baby of the furniture magnate he previously stole; and The Big Lebowski‘s Jeff Lebowski, who winds up sans rug, sans one of his best friends, and sans the million dollars he was promised (but with johnson thankfully intact).

The shocking thing about the climactic ending of No Country for Old Men is that the Coen Brothers don’t even bother to show it onscreen. Why?

Well, partially they’re just being faithful to Cormac McCarthy’s novel of the same name. But certainly this ending appealed to Joel and Ethan for a good reason: it’s the real ending. Of course Llewelyn Moss is going to get his ass handed to him. You and I — the ones who sit in traffic on the way to work every day wishing there was a way to leave the rat race behind — we read stories about idiots like Llewelyn Moss all the time. They’re the ones who you see doing the perp walk on the evening news, the ones who thought they could beat the odds, the ones who thought they could get away with it. You and I know that there’s only one place where a stubborn Texas welder with a shotgun can outsmart, outmaneuver, and outgun a Mexican drug cartel: Hollywood.

And most Hollywood directors are there specifically to indulge these fantasies for us. That’s why we fork over ten dollars every few weeks, so we can see the story of the guy who beat the odds. To see the promise of the American Dream fulfilled. Hollywood obliges by giving us that one-man-against-an-army scenario time after time on the big screen. After the lights come on, you’re going to go back to your middle-class job with your scheduled annual 5 percent raise, but you can be comforted that somewhere out there, some underdog beat the odds.

One of the reasons I love the Coen Brothers is because they refuse to play this game. They refuse to peddle the same bullshit. They know how the world works, and with No Country for Old Men, they give us a much-needed splash of cold reality. It’s very simple. You play with fire, and you’re going to get your head blown off by a cattle gun.