Norman Spinrad recently wrote a review in Asimov’s of my novel Infoquake wherein he discussed the scientific accuracy of the book. Mr. Spinrad had this to say:

[W]hether or not such a novel could be considered “hard science fiction”… might be moot if Edelman himself were just blowing rubber science smoke and mirrors. Instead, he is actually trying to make bio/logics and MultiReal seem scientifically credible in the manner of a hard science fiction writer and doing a pretty good job of it, at least when it comes to bio/logics.

Edelman seems to have convincing and convincingly detailed knowledge of the physiology and biochemistry of the human nervous system down to the molecular level. And cares about making his fictional combination of molecular biology and nanotech credible to the point where the hard science credibility of the former makes the questionable nature of the latter seem more credible even to a nanotech skeptic like me.

A week or so later, SF Diplomat took a potshot at the scientific credibility of the book in his smackdown of Spinrad’s piece, saying that though the book is enjoyable enough, “Infoquake is practically fantasy.”

This has led me to give some thought about the scientific credibility of Infoquake and the scientific credibility of science fiction in general. Should the reader care whether my book — or any SF book — has good science?

For the record, my knowledge of science is fairly rotten. I don’t have the foggiest idea what the spleen does, I can’t really tell you anything about Planck’s constant, and I had to put down A Brief History of Time about 40 pages in because I was overwhelmed. As you might imagine, I’m very pleased that Spinrad thought I have “convincingly detailed knowledge of the physiology and biochemistry of the human nervous system down to the molecular level.” Greg Egan and Arthur C. Clarke are probably climbing into graves right now specifically for the purpose of rolling over in them.

But when I started the process of writing Infoquake, my intention was to write a novel about high-tech sales and marketing. It was only supposed to be accurate insomuch as it wasn’t supposed to make people with real scientific knowledge snicker. So I set the book at some undefined time in the future, about a thousand years from now, and I stuck an apocalyptic AI revolt in the interregnum to really wipe the slate clean. Then I made three suppositions:

- Give the scientists (virtually) unlimited computing power.

- Give the scientists (practically) inexhaustible energy reserves.

- Give the scientists a few hundred years to tinker, without all the regulatory, governmental, religious, and socioeconomic chokeholds in place today.

Supposing all that… What kind of world would we end up with?

I started doing my initial research through your typical high-level Encarta searches and the like (Wikipedia wasn’t around then). And I discovered that we’re really, really close on so many “science fictional” technologies already. Teleportation? We’ve got teleportation, believe it or not. (Okay, so it’s only on a quantum level at this point, but why quibble?) Orbital colonies, medical nanobots, virtual reality, and neural manipulation? All possible, based on the evidence we have now.

There are a million possible technologies out there whose only real barriers are time and economics. Why aren’t we all flying around in personal spaceships by now like Heinlein, Asimov, Bradbury, and Clarke predicted we would be? Because these authors didn’t have scientific chops? No, because it’s too fucking expensive, that’s why. We have flying cars and jetpacks and space stations and the like, they just haven’t proven practical enough to mass produce. And unfortunately, nobody really had any way of knowing that they weren’t practical until the engineers sat down at the drawing board and tried to do it.

There are a million possible technologies out there whose only real barriers are time and economics. Why aren’t we all flying around in personal spaceships by now like Heinlein, Asimov, Bradbury, and Clarke predicted we would be? Because these authors didn’t have scientific chops? No, because it’s too fucking expensive, that’s why. We have flying cars and jetpacks and space stations and the like, they just haven’t proven practical enough to mass produce. And unfortunately, nobody really had any way of knowing that they weren’t practical until the engineers sat down at the drawing board and tried to do it.

I’m convinced that the same is the case with the technologies in Infoquake. Take the multi network, for instance, wherein you’re fooled through nanotechnological neural manipulation into believing that you’re somewhere you’re not. Scientifically feasible or infeasible?

From a theoretical standpoint, we can practically build the multi network already. Put someone on a slab in the ER, saw off the top of their skull, and start stimulating pieces of brain tissue with tiny electrodes; they’ll start seeing and hearing things. So why don’t we have a functional multi network today? Because we need (1) much smaller electrodes, (2) much more detailed mapping of which pieces of the brain do what, and (3) ultra-fast computers that can keep track of all this information and manipulate it in real time. Once we have that: voila! Virtual reality! Right?

Obviously, once someone digs in there and tries to build something like this, they’re going to discover that it’s not quite that simple. There might be no practical way to power those electrodes, for instance, or maybe there’s some bit of brain chemistry we don’t quite understand yet that will make it impossible to host lots of little nanobots inside your skull. We’re going to have to wait for the chemical engineers to synthesize a finer type of wiring, which will require access to cheap cobalt from Bolivia, which is impossible because Bolivia’s in a state of civil war, which is caused by blah blah blah et cetera ad nauseum.

That’s life. That’s the slow march of progress. All we can do in the meantime is theorize and then sit back and hope the results in the lab match the equations on the chalkboard.

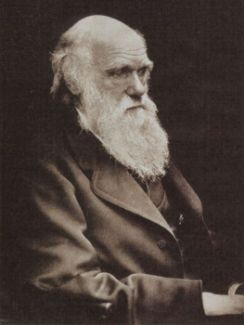

I often think about the 19th century debate in scientific circles between the Darwinian and Lamarckian models of evolution. Take the evolution of the giraffe. Jean Baptiste-Lamarck figured that a lifetime of stretching and craning his neck to get that good stuff high up in the trees would actually alter a giraffe’s biochemical composition. The giraffe would then pass on some kind of beefed-up genetic heritage to its offspring, causing the species to evolve over time with a longer neck. Darwin came along later and said that what the giraffe does makes little difference. The reason the species evolves is because the giraffes with taller necks are more likely to survive and thus pass on the tall-neck genome.

I often think about the 19th century debate in scientific circles between the Darwinian and Lamarckian models of evolution. Take the evolution of the giraffe. Jean Baptiste-Lamarck figured that a lifetime of stretching and craning his neck to get that good stuff high up in the trees would actually alter a giraffe’s biochemical composition. The giraffe would then pass on some kind of beefed-up genetic heritage to its offspring, causing the species to evolve over time with a longer neck. Darwin came along later and said that what the giraffe does makes little difference. The reason the species evolves is because the giraffes with taller necks are more likely to survive and thus pass on the tall-neck genome.

Both of these explanations sound perfectly plausible. I’m sure Lamarck had plenty of reason for believing what he believed, and in fact, his theory was widely accepted as truth for fifty years. Now it turns out that Lamarck was wrong on this particular business, and Darwin was right. But again, there was really no way for anyone to know that right off the bat until generations of scientists kept digging through fossils and Gregor Mendel did his whole thing with gardening peas. There are still a few stubborn holdouts who don’t accept Darwinism.

And that’s the thing that laypeople tend to forget about science. The guy shouting “Eureka!” and madly scribbling equations on the chalkboard is only the first step in a very, very long process. Scientists need to get in the lab and get their hands dirty. They need to collect evidence and subject that evidence to rigorous tests. They need to present that evidence before their peers in scientific journals. All kinds of alternative explanations need to be thoroughly vetted and debunked. And all of that stuff takes time. Years, decades, centuries. There’s a reason why it’s called the Theory of Evolution, just like there’s a reason why it’s called the Theory of Gravity.

The real world tends to get in the way too. Scientists’ funding gets cut. Their agendas for pursuing particular lines of research get questioned. Governments come in and make executive decisions about what science they can pursue and what science they can’t. Security issues abound. Patents must be filed, lawsuits must be litigated.

And when you’re a science fiction writer, of course, you don’t have time to do any of that. All you can do is the very first step, which is to try to recreate that proverbial “Eureka!” moment when the guy runs to the chalkboard and scribbles out his equations. We don’t know what’s going to happen in the laboratory to support our theories. We don’t know how the fossil evidence is going to weigh in. We can only offer vague conjectures about how much it’s all going to cost.

So anyone who believes they’re reading an accurate depiction of the future in a science fiction novel is deluding themselves. Future science has too many unknown variables for anyone to possibly predict. If we do end up someday breeding über child warriors to fight bug aliens on virtual terminals in outer space a la Ender’s Game, I’m sure Orson Scott Card will be the first one to admit that he was just lucky.

As for Infoquake, you can call it fantasy or you can call it science fiction. I don’t really care. I would just caution against mislabeling it for the wrong reasons.