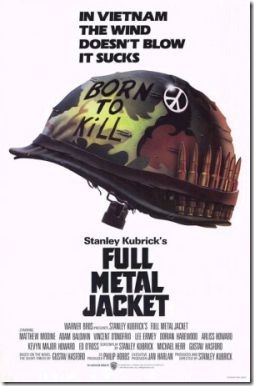

Nobody seems to be paying attention to the fact that 2007 marks the 20th anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Warner Home Video finally released a deluxe 2-DVD edition just last week, along with remastered editions of The Shining, 2001, A Clockwork Orange, and a few others.

Why is it a shame that nobody’s marking the occasion? Because Full Metal Jacket is one of the most meticulously crafted films of the past 20 years. I think it’s damn near perfect.

(Interesting side note: Believe it or not, this will be Full Metal Jacket‘s first home video release in widescreen. The film was originally shot in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, what you and I call “widescreen.” But if you’re an eccentric genius like Stanley Kubrick, you get to make unconventional decisions. Before his death Kubrick decided that, since 98% of the world’s TV sets back then had a 4:3 aspect ratio — i.e. “fullscreen” — henceforth and forevermore his films would be released in a 4:3 aspect ratio. None of that devil letterboxing for Stanley! It’s only now that Warner Home Video, with the collaboration of the Kubrick estate, is restoring the films to their original specs.)

(Interesting side note: Believe it or not, this will be Full Metal Jacket‘s first home video release in widescreen. The film was originally shot in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, what you and I call “widescreen.” But if you’re an eccentric genius like Stanley Kubrick, you get to make unconventional decisions. Before his death Kubrick decided that, since 98% of the world’s TV sets back then had a 4:3 aspect ratio — i.e. “fullscreen” — henceforth and forevermore his films would be released in a 4:3 aspect ratio. None of that devil letterboxing for Stanley! It’s only now that Warner Home Video, with the collaboration of the Kubrick estate, is restoring the films to their original specs.)

Audiences have had a peculiar relationship with Full Metal Jacket since its debut on July 26, 1987. It’s much loved in some quarters, but it’s equally despised in others. Everyone seems to appreciate the taut first act set in a Parris Island Marine boot camp, yet many never get over the film’s sudden shift to Vietnam in its second half. Even so perceptive a critic as Roger Ebert famously called the latter half of Full Metal Jacket “a series of self-contained set pieces, none of them quite satisfying.”

But Full Metal Jacket is designed to be a two-part story; just about everything you see in the first half of the film has a parallel in the second. It’s a structure Kubrick has used before (cf. the apes/the astronauts in 2001, and Alex’s life before/after his treatment in A Clockwork Orange).

More than that, the film is full of dualities: Joker’s helmet with the peace symbol and “Born to Kill” inscribed on the side (“I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man… The Jungian thing, sir”). The two dramatic deaths at the end of each section. The two-mindedness of the American public about the war. Joker’s own conflicting desires to “get into the shit” and to get out of there as quickly as possible. His dual nature as Leonard’s teacher and as the one who beats Leonard the hardest. And so on.

Of course, most of the moviegoing public doesn’t want to see films about Jungian dualities, and so people often go into Full Metal Jacket with false expectations. Hollywood generally only gives us three categories of war films: (1) the anti-war film (Platoon, Kubrick’s own Paths of Glory) (2) the war-is-sordid-but-necessary-and-sometimes-ennobling film (Saving Private Ryan), and (3) the out-and-out propaganda film (John Wayne’s The Green Berets, 300). But what do you do with a Vietnam movie that not only refuses to take a stand on the Vietnam War, but actually embraces its contradictions? “Do I think America belongs in Vietnam?” Crazy Earl says in response to a question from the television interviewers in FMJ. He looks totally perplexed, like he’s never even considered the question before. “I don’t know. I belong in Vietnam, I’ll tell you that.”

So if you’re going to get the most out of Full Metal Jacket, be prepared to take the long view. The way long view, the view of an alien civilization dispassionately studying humanity under a microscope. Like those hypothetical aliens, Kubrick rarely makes moral judgments; he simply observes. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, Joker, Animal Mother, the Vietnamese sniper, even the crazy gunner gleefully shooting down fleeing Vietnamese civilians from a moving helicopter — the film doesn’t really take anybody’s side. It doesn’t give you convenient moral labels to tell you who the good guys and who the bad guys are.

Take Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played with vicious brio by R. Lee Ermey (you know, the guy who’s played the military drill sergeant in every fucking movie since 1987). At first blush, he seems like as good a candidate as any for a villain in this movie. A manipulative brainwasher, a callous tool of the U.S. government. But on repeated viewings, you realize that he’s not the villain at all — quite the opposite. He’s doing his best to prepare these soldiers to survive out in the field. He’s a father figure. He’s a protector and teacher. He’s Obi-wan Kenobi, if Obi-wan Kenobi called his Padawan learners “unorganized grabastic pieces of amphibian shit.”

“Because I am hard you will not like me,” says Hartman. “But the more you hate me, the more you will learn.” Didn’t Mr. Miyagi say something similar to the Karate Kid when making him paint the fence?

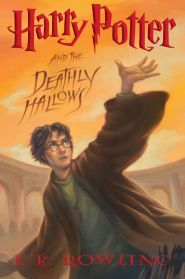

I predicted that Harry, Ron, and Hermione would all live to the end of the series, though J.K. would keep us in suspense until the last minute. Bing! I predicted that Snape would reveal that he had killed Dumbledore and turned Death Eater on Dumbledore’s orders. Bing! I predicted that Harry would triumph over Voldemort at the expense of lots of secondary characters. Bing! I predicted that Harry would find some way to contact Sirius Black again from beyond the grave. Well, no bing! there, but I’d suggest that I deserve a partial bing! since Harry does manage to contact another dead mentor (Dumbledore) from beyond the grave.

I predicted that Harry, Ron, and Hermione would all live to the end of the series, though J.K. would keep us in suspense until the last minute. Bing! I predicted that Snape would reveal that he had killed Dumbledore and turned Death Eater on Dumbledore’s orders. Bing! I predicted that Harry would triumph over Voldemort at the expense of lots of secondary characters. Bing! I predicted that Harry would find some way to contact Sirius Black again from beyond the grave. Well, no bing! there, but I’d suggest that I deserve a partial bing! since Harry does manage to contact another dead mentor (Dumbledore) from beyond the grave.