An ordinary guy finds a suitcase full of thousand dollar bills. There’s no one around. Instead of going to the cops, the guy figures it’s his lucky day and takes the money. Which works just dandy until the big bad motherfuckers who own the suitcase decide to come looking for it.

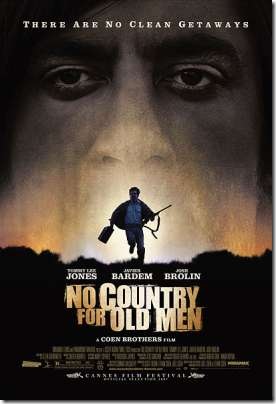

You’ve seen that film a thousand times before, and it’s essentially the plot of Joel and Ethan Coen’s brilliant new film, No Country for Old Men (based on the Cormac McCarthy novel of the same name). It’s one of the standard thriller plots that crawls out of Hollywood every five years dressed up in a slick suit of violence with a little flower of moral conundrum stuck to its lapel. The Coens have entertained a few variations on the suitcase-of-money scenario themselves (see Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and The Ladykillers).

You’ve seen that film a thousand times before, and it’s essentially the plot of Joel and Ethan Coen’s brilliant new film, No Country for Old Men (based on the Cormac McCarthy novel of the same name). It’s one of the standard thriller plots that crawls out of Hollywood every five years dressed up in a slick suit of violence with a little flower of moral conundrum stuck to its lapel. The Coens have entertained a few variations on the suitcase-of-money scenario themselves (see Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and The Ladykillers).

Here’s the thing. No Country for Old Men took that dandy little thriller behind the woodshed and beat its ass bloody.

That No Country for Old Men is fiercely entertaining is not really the point. Some audiences can’t see past the offbeat humor and treat the Coen Brothers’ films like hip Quentin Tarantino trifles. Critics often fail to see the point too. They’ve labeled the work of the Coens nihilistic, or misanthropic, or just plain vicious. They call the Coens’ films empty exercises in technical virtuosity without soul or subject.

These critics couldn’t be more wrong. Joel and Ethan Coen have an ongoing subject, and it’s a subject that they discuss intelligently and with compassion. Their subject? The American Dream.

You know, the American Dream: the idea that any penniless schlub born in a broken-down shack can, through grit and hard work, one day become Andrew Carnegie, or Sam Walton, or Bill Gates. It’s a free country! Opportunities unlimited! There’s supposed to be a proper moral framework propping up the whole thing, but somehow in the latter half of the twentieth century it became all about the money. Americans are obsessed with the stuff, whether in the affirmative sense (money enables you to follow your hopes and dreams) or in the negative sense (money can’t buy you happiness). Either way, material wealth always seems to be the fulcrum around which the whole American moral universe teeters. Rather appropriate when you think about it, considering that the United States was largely founded by a bunch of rich white landowners who were pissed off at the King of England because their taxes were too high.

Regardless, the American Dream is what it is, and for whatever reason Joel and Ethan Coen seem to have chosen it as their topic. In film after film, ever since 1984’s Blood Simple, the Coens have been steadily dissecting this Dream. Analyzing it, tearing it up, and stitching it back together. Charting out the ways it can corrupt us and demean us.

Witness Fargo, the story of a dumbass car salesman whose shame about his inability to provide a better life for his family leads him to fraud, extortion, and ultimately murder. Witness The Hudsucker Proxy, a cartoony take on Frank Capra in which a naive dimwit strives to reach the top of a major corporation only to find himself the puppet of his corporate masters. Or The Big Lebowski, featuring a ’60s reject with no ambition higher than getting his rug back, who is nonetheless sucked into the scheme of a corrupt self-styled philanthropist to steal a million dollars. Or The Man Who Wasn’t There, starring yet another dim bulb who’s thrust unprepared into a world of ambition by his wife’s philandering and is ultimately undone by it.

What do all the Coen protagonists have in common? They’re all ambitious schemers dissatisfied with the status quo, looking for unorthodox ways to achieve that American Dream.