Here are a few things that every American knows.

- The world is a vile and dangerous place.

- America is blindly and irrationally hated by just about everybody outside of our borders.

- If we left our security up to the peaceniks, bureaucrats, and Boy Scouts we elect to national office, the United States would be a smoldering ruin in a matter of months.

- Therefore it’s necessary that we fund a zillion intelligence agencies and black ops teams who routinely conduct secret assassinations in the name of defending our country.

- Nevertheless, despite our massive economic and military power, the United States is drastically outnumbered and constantly on the verge of apocalypse.

At least, these are the assumptions behind just about every spy thriller ever made. Now I find myself wondering: When the hell did these assumptions become so ingrained in our psyche? When did we blithely start accepting this worldview? Who says the United States should behave this way — and, for that matter, when did we all decide that the United States actually does behave this way? What the fuck happened to my country?

At least, these are the assumptions behind just about every spy thriller ever made. Now I find myself wondering: When the hell did these assumptions become so ingrained in our psyche? When did we blithely start accepting this worldview? Who says the United States should behave this way — and, for that matter, when did we all decide that the United States actually does behave this way? What the fuck happened to my country?

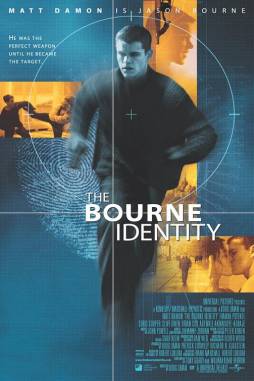

These assumptions are also the ones that underline 2002’s The Bourne Identity. It’s a nice little popcorn flick with a plot so familiar you can slip into it like an old bathrobe. Matt Damon plays Matt Damon, playing a CIA-funded black ops assassin who has a change of heart because the agency has Gone Too Far. Now after a bout of amnesia, he finds himself on the run from the very organization that funded him. Car chases and dead bodies ensue. Spoiler alert: the heroic Matt Damon gets the girl, and the villainous Chris Cooper gets shot in the head. (Oh, and FYI, there are more spoilers below.)

And then someone had the inspired idea of hiring Paul Greengrass (Bloody Sunday, United 93) to take over the franchise. To call The Bourne Supremacy and The Bourne Ultimatum better films than their predecessor is kind of like calling a fine aged pinot grigio better than a Zima. They’re among the most intelligent, well-crafted, thoughtful thrillers about American paranoia that I’ve ever seen. (And holy crap, did you realize Matt Damon could act?)

Suddenly our protagonist is no longer just a youthful maverick spy fleeing across Europe with a spunky German chick in tow. Jason Bourne is not so much a character in Supremacy and Ultimatum as he is a manifestation of the American subconscious. He’s an unstoppable force who never tires, who never gives up, who can never be killed. Imagine a cross between Batman and Patrick Henry who knows how to kill people with a plastic pen.

Richard Corliss clearly noticed the transformation in his Time magazine review of The Bourne Ultimatum:

That’s the secret of this character, and Bond and John McClane and all the other action-movie studs. They are a projection of American power — or a memory of it, and the poignant wish it could somehow return. In real life, as a nation these days, we can achieve next to nothing. But in the Bourne movies just one of us, grim, muscular and photogenic, can take on all villains, all at once, and leave them outwitted, dead, disgraced. That’s a macho fantasy of the highest, purest, most lunatic order.

Corliss is on to something here, but I think he’s got it exactly backwards. Jason Bourne isn’t just an action stud in the James Bond mold; Bourne is, in fact, a calculated response to James Bond, or more than that, he’s the anti-James Bond. James Bond on the Bizarro planet. Is it an accident that Jason Bourne and James Bond have the same initials? (Well, actually it probably is. But you’d have to ask Robert Ludlum, who created the character, and he’s dead. But apparently Greengrass didn’t read the Ludlum novels anyway.)