This book review was originally published in the Baltimore Evening Sun on July 19, 1993.

This book review was originally published in the Baltimore Evening Sun on July 19, 1993.

Any doctor that prescribed five enemas a day, sexual abstinence, and high doses of radium exposure for an ulcer would be kicked out of town before sunset.

Unless, of course, that doctor was Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and that town was Battle Creek, Michigan in the year 1907. There Kellogg, the self-proclaimed health messiah and inventor of corn flakes and peanut butter, reigned supreme. For over twenty years, Kellogg’s sanitarium devoted to “scientific living” attracted the best and brightest of Americans out to find the magic cure for disease and death. Celebrities like Thomas Edison, Upton Sinclair, and Henry Ford all tried their hand at Kellogg’s prescription, which included all of the above as well as strict vegetarianism, electric shocks, laugh therapy, and more.

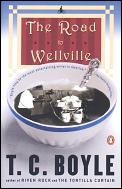

This preposterous medical regime and the man that inspired it serve as the subject for T. Coraghessan Boyle’s latest novel, The Road to Wellville. Under Boyle’s razor-sharp pen, Kellogg is reduced to a shallow, self-serving hypocrite who is more out to promote his dubious brand of morality than heal the sick.

Yet Boyle, who is also the author of East Is East and the PEN/Faulkner Award-winning World’s End, doesn’t content himself with such an easy target as Kellogg. Instead, he uses Kellogg’s antics as the basis for a hilarious satire about people still abundant in our society today: holier-than-thou healthmongers, the con men who profit off them, and the suckers that swallow both of their lines hook and sinker.

Wellville’s protagonist, Will Lightbody, has been dragged out to Battle Creek by his wife Eleanor, a bored housewife who takes up causes like others take up macramé. She convinces the hesitant Will that Kellogg’s program can cure both his stomach ailment and her frayed nerves. Soon Will is snared in a retreat full of eccentric vegetarians trying to force their bizarre lifestyle down his throat, despite the fact that it isn’t helping his stomach at all. He moves from the milk diet to the grape diet and then back again, all without success.

Meanwhile Eleanor quickly takes a frenzied dive off the deep end, indulging in every half-baked therapy from starvation diets to nude sunbathing to “womb manipulation.” Kellogg and his cronies convince her that it might take a while for her nerves to recover from eating all those evil steaks and poisonous alcoholic beverages she used to enjoy. It might even take years.

The other plot which runs concurrently to the Lightbodys’ chronicles the misfortunes of would-be breakfast food tycoon Charlie P. Ossining. The young Ossining arrives in Battle Creek ready to make a million dollars marketing Per-Fo Corn Flakes, the ultimate nutritious breakfast food. Unfortunately, Ossining makes one mistake: he takes on con man Goodloe Bender as a partner. Bender is soon off spending the company’s bank account on “business dinners” and “investment opportunities” while sending Charlie out to do the “important work” — like wandering around town wearing sandwich boards to advertise their non-existent product.

Luckily, the Per-Fo Company finds an ace in the hole: the drunken, disowned son of John Harvey Kellogg has agreed to come on board and attach the prestigious Kellogg name to their corn flakes. George is Kellogg’s Achilles’ heel, a huge besotted embarrassment to all the Doctor’s claims to progressive and rational living. He’s the one thing that Kellogg can’t control and can’t get rid of.

If there’s a problem with Wellville’s diagnosis of society’s health police, it’s that the author comes up with no effective recovery plan. The book’s ending pits Kellogg’s ludicrous brand of hyper-civilization against animal brutishness that’s equally disturbing. If the savage impulses of violence and male domination really do underlie human endeavors, then this is a dark ending indeed. Perhaps it’s intended as a last-minute pitch of sympathy for the poor, ignorant Dr. John Harvey Kellogg: at least he tried.