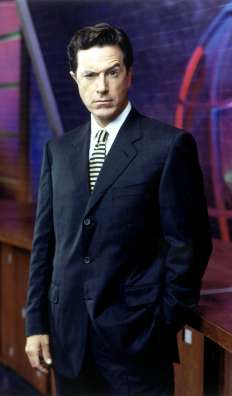

Stephen Colbert had an amusing rant the other week about how the world is turning into a wiki. Everybody has the power to edit reality, said Colbert. If you don’t like the way the world works, just log in to Wikipedia and change it.

He’s almost right. If you don’t like the way the world is, now you can edit your version of it with Greasemonkey.

He’s almost right. If you don’t like the way the world is, now you can edit your version of it with Greasemonkey.

Greasemonkey, in case you don’t know, is a plug-in for the Mozilla Firefox browser that lets you write little Javascripts to run on web pages after they’ve been downloaded to your browser. It’s become quite popular with the Slashdot crowd.

Sounds techno-wonky? Something that only the dude in the back room configuring the Linux servers would care about? No. Hold onto your hats, folks, because Greasemonkey is your future. It’s the harbinger of a serious change in how the world functions, and in forty years you’re going to wonder how you ever lived without it.

Let’s just start with what the Greasemonkey plug-in is doing today.

On my browser, I have a Greasemonkey script called Linkify Plus installed. This script silently searches through every web page I download for web and e-mail addresses that haven’t been hyperlinked, and it hyperlinks them. So for instance, every time I see dedelman@gmail.com on a web page, the Linkify Plus script automatically turns that into dedelman@gmail.com — whether the creator of the page wanted that text hyperlinked or not.

And why should the author of the page care? After all, when you access a page on the web, you’re downloading a copy of it. Your own copy, to do with whatever you please. If you want to open up that page on your own machine and change the code, resize the pictures, or rewrite the text, that’s your right. I have a friend who writes little rants in the margins of his books to the authors when he finds something he disagrees with. Nothin’ wrong with that. Greasemonkey just automates the process.

(I should point out that Greasemonkey didn’t invent this functionality; they’ve just popularized it. All modern browsers have the capability of changing a page’s display through custom style sheets. And before I get bombarded with snarky comments, let me point out that Opera can run Greasemonkey scripts too.)

So Greasemonkey makes it easy to tweak web pages on the fly. Why stop with just style and display changes? Why not change the content?

Take this Greasemonkey script that I’ve just written, which I’m going to call Brockify in honor of David Brock. (Brock spent many years as a sleazy right-wing mudslinger until he switched sides and became a sleazy left-wing mudslinger instead.) My Brockify script will silently swap the words “liberal” and “conservative” for you on any page on the web. Go ahead, install the Greasemonkey plug-in and the script, then test it out. (And for God’s sakes, don’t forget to turn it off when you’re done.) It’s seamless and it’s almost instantaneous. You’ll see Rush Limbaugh is now bemoaning those “conservative pinheads,” while Al Franken has taken to griping about “liberal religious fanatics.”

The Washington Times always refers to gay marriage as gay “marriage.” This annoys the crap out of me; it’s blatant editorializing, and distracting as hell in the context of a straight news story. (No pun intended.) But now I can write a Greasemonkey script and remove the belittling quotation marks once and for all.

These are fairly crude examples, but you see my point. With a simple script, you can customize, bowdlerize, sanitize, and homogenize the web.

Now here’s where things get fun.

The Greasemonkeying of information won’t just stop with the web. It’s not going to end with the editing of digital bits on your computer screen. It’s going to move onto your telephone and your television and eventually, inside that thick skull of yours.

What happens when you call up your bank to check your balance? The nice pre-recorded white lady asks you to read your account number out loud, and software on the bank’s servers turns your voice into 1’s and 0’s that the computer can understand. The software parses through that information and finds your credit card number.

But once you’ve reduced speech to a bunch of digital bits, who’s to say you can’t Greasemonkey it?

Here’s how it might work for the typical consumer. You buy a phone with parental protections and hand it to your fourteen-year-old. The phone’s got a speech recognition program inside that instantly takes the voice on the other end and runs it through a Greasemonkey script. This script searches the caller’s voice for the “f” word and instantly bleeps it out, before the caller has even finished saying it. Or maybe the script compares the caller’s voiceprint against a database of registered sex offenders and calls the cops if it finds a match. Hell, maybe you’ve compiled your own database of Those Long-Haired Pricks That Your Daughter Is Not Going Near If You Can Help It.

Sounds far-fetched? Hardly. If Citibank can do it today, then with all the advances in computing power and miniaturization coming up in the next two decades, you’ll be doing it on your Verizon phone by 2020. And that’s a conservative estimate.

The same thing could very easily work on your TV too. Want to completely eradicate racial epithets from television programming? Easy. Install the Cosbyizer on your next generation TV and let it automatically filter out the “n” word for you. (And because the Cosbyizer has licensed technology from Pixar, it can even redraw pixels on the screen to make the speakers’ lips move in sync.)

Isn’t this censorship? you’ll ask. What about the First fucking Amendment?

And the answer will be: Of course it’s not censorship. The First Amendment doesn’t apply when you choose to censor yourself, does it? And don’t parents automatically act as something of a Greasemonkey script anyway? Isn’t filtering out harmful content from their children’s eyes and ears what parents do?

But there’s a whole Big Brother aspect to this that’s hard to ignore. More and more of our communication takes place on screens and speakers. We talk to our officemates across the hall over IM instead of walking over there; we pick up the phone and call our co-workers across the country. All these intermediary devices are potential hosts for Greasemonkey scripts. Some day soon, a company’s going to insist that all intra- and extra-company communication go through their Greasemonkey scripts to limit their liability. You’ll no longer have to worry about that nondisclosure agreement that limits you from telling outsiders about widget X; you won’t be able to tell outsiders about widget X, because the Greasemonkey script will edit you first.

Now I’m gonna get really science fictional on your asses.

Your experience of the world essentially comes from your five senses. What are your eyes but a human filter, a way of translating random splotches of light into a format that your brain can understand? Ditto your ears. All this information passes into the brain as electrical pulses in the nervous system. Who’s to say you can’t stick a chip in your head that runs — you guessed it — a Greasemonkey script?

Clarify your vision or eradicate your colorblindness with a Greasemonkey script that rewrites the signals going to your brain. We’re already doing it with hearing (as Michael Chorost’s brilliant Wired article demonstrates). How long before you’ll be able to literally rewrite the world around you? Change your girlfriend’s blond hair to brunette. Lower the pitch on your boss’s voice so he doesn’t sound so whiny. Edit the font on the street signs you pass every day just for kicks.

(Allow me to insert the obligatory plug for my novel Infoquake here. The book is essentially all about that trippy-scary future, where people can run programs like EyeMorph 66 and PokerFace 43 on their nervous systems.) (Don’t want to see any more obligatory plugs for Infoquake? Write a Greasemonkey script and edit them out.)

We all experience a different reality. That’s been true since the dawn of humankind. But in the coming century, our realities will get personalized beyond anything you or I could possibly imagine.

Just ask my good friend, the liberal commentator Rush Limbaugh.