William Gibson has said many times in interviews that he knew very little about computers when he wrote his groundbreaking, genre-spawning novel Neuromancer. And yet somehow, all the way back in 1984 he managed to not only anticipate things like Internet culture and wetware, but to understand them better than many of us do even today.

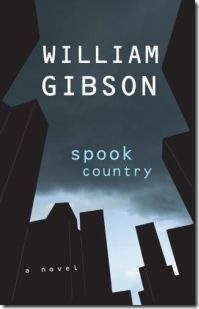

Despite the fact that he’s now a best-selling — nay, legendary — author, I doubt that William Gibson knows much more about international crime and high-tech freelance spies than you or I do. And yet somehow, in his latest novel Spook Country, he manages to not only understand this world, but to extrapolate it and scope out its implications better than anyone else.

Despite the fact that he’s now a best-selling — nay, legendary — author, I doubt that William Gibson knows much more about international crime and high-tech freelance spies than you or I do. And yet somehow, in his latest novel Spook Country, he manages to not only understand this world, but to extrapolate it and scope out its implications better than anyone else.

Look at how effortlessly he explores a new medium called “locative art.” Locative art is what happens when you mash up GPS units and virtual reality. Think Second Life, if the whole thing was overlaid on top of the real world and accessible through 3D goggles.

The concept of locative art is cool enough. But Gibson’s genius isn’t that he can think up this cool new technology; it’s that he already knows how we’re going to use it. In the first chapter of Spook Country, a locative artist demonstrates the technology by showing a holograph of River Phoenix’s corpse lying face down on the sidewalk — in the exact place where River Phoenix’s corpse actually lay face down on the sidewalk.

Now that’s cool.

(At the risk of self-pimping, let me mention that this locative art technology has a lot of similarities to the multi network I mention in my own novels. Except in my books, the “multi projections” you see in the real world are the result of an imaginary nanotechnological system called the OCHRE network. In Gibson’s book, this is real. Indeed, he supposedly consulted with high-tech wizard Cory Doctorow on the details. You could head out to Radio Shack and build a Spook Country-style work of locative art with a laptop today. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone’s doing it right now.)

The story of Spook Country is really the same story that William Gibson has been telling in all his novels since Neuromancer. It’s remarkable how similar all these books are structured. Take a somewhat jaded young professional, and throw her in the middle of a struggle between mysterious powers way over her head. Sometimes these powers are hyper-intelligent AIs, sometimes they’re multinational corporations, sometimes they’re anonymous government agencies. The conflicts they engage in always involve lots of money being thrown around and the use of cutting-edge technology.

The three jaded POV characters in Spook Country are Hollis Henry, a former cult rock musician turned journalist; Tito, an operative in a boutique Cuban-Chinese crime family; and Milgrim, a junkie who’s been forcibly “recruited” to serve as the translator for a rather vicious CIA type named Brown. Our three protagonists become involved in a clandestine spy game going on between two unnamed freelance espionage forces. What exactly the game is Gibson doesn’t reveal until the book’s final pages, but it involves stolen iPods, geohacking, and a race to locate one very particular crate that’s floating on some ship somewhere in the world. (What’s in the crate? I won’t spoil it, and it doesn’t really matter that much anyway — but I will admit to feeling slightly let down by the revelation.)

In a way, Gibson’s vision of the world isn’t so much different from Philip K. Dick’s. Both envision a world of Little People being tossed around by enormous godlike forces. But while Dick’s characters are paranoid survivors just hanging on to the edge of sanity, Gibson’s have a certain groundedness and indomitable spirit. Hollis Henry and Henry Case and Cayce Pollard and Berry Rydell may not know exactly what game it is they’re playing, but through the course of a Gibson novel they learn how to hustle it. They may get buffeted around by the forces above, but in the end they’re rewarded for it.

It’s interesting how, even though Gibson’s worlds are often called “bleak” and “dystopian,” his novels really don’t deal with moral ambiguity, which is supposed to be a hallmark of modern storytelling. These descriptions are really quite misleading, because he’s actually a very traditional storyteller. Your standard Gibson protagonist is not an anti-hero, and your standard Gibson villains are not sympathetic. We have no trouble in Spook Country identifying who the good guys are and who the bad guys are; the instant you see Brown pushing Milgrim around, you can tell he’s up to no good. Likewise Gibson protagonists aren’t seriously tempted by the Dark Side. They may skirt the law, but they remain decent to the core. (And isn’t the law just a tool of the multinationals anyway?)

It’s interesting how, even though Gibson’s worlds are often called “bleak” and “dystopian,” his novels really don’t deal with moral ambiguity, which is supposed to be a hallmark of modern storytelling. These descriptions are really quite misleading, because he’s actually a very traditional storyteller. Your standard Gibson protagonist is not an anti-hero, and your standard Gibson villains are not sympathetic. We have no trouble in Spook Country identifying who the good guys are and who the bad guys are; the instant you see Brown pushing Milgrim around, you can tell he’s up to no good. Likewise Gibson protagonists aren’t seriously tempted by the Dark Side. They may skirt the law, but they remain decent to the core. (And isn’t the law just a tool of the multinationals anyway?)

One thing to be prepared for in Spook Country is the spareness of the prose. Gibson seems to be moving towards a crisper, punchier style that relies less on intricate wordplay and more on snappy dialog. Most of the chapters are short — sometimes only a page or two long — and they generally end with some kind of twist to get you turning the pages. It’s the kind of tactic you find in the pulpier thrillers that sit next to the supermarket checkout counter, and I might have been disappointed to see Gibson using it if he hadn’t thoroughly mastered the technique better than any supermarket thriller I’ve read.

If there’s a downside to Spook Country, it’s the same downside that mars just about all of Gibson’s novels. He tends to get tangled up in plot somewhere around the two-thirds mark of each book, and you find yourself struggling to just figure out what the heck is going on, much less figuring out what it all means.

But don’t let that scare you off reading Spook Country (or indeed any of Gibson’s works). That just means you might want to flip right back to the first page after you’ve finished to read the book again. Which I’ll certainly be doing soon.