J.R.R. Tolkien did not write The Lord of the Rings or any of the related Middle Earth materials. Honestly.

No, the good Oxford don was merely a translator and annotator of an ancient work of literature known as the Red Book of Westmarch. In addition to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, which are presumed to have been written by Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, the Red Book also contained a large collection of ancient folklore known as Translations from the Elvish. It’s from this section of the Red Book that The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, and Unfinished Tales are presumed to have originated.

To me, this is one of the truly fascinating things about Tolkien’s world that sets it on a higher pedestal than just about any other work of fantasy. Middle Earth extends beyond the printed page. Like the actor who stays in character between performances, Tolkien pretended in his letters and private writings that he really was just a quaint British scholar dusting off old books of lore.

To me, this is one of the truly fascinating things about Tolkien’s world that sets it on a higher pedestal than just about any other work of fantasy. Middle Earth extends beyond the printed page. Like the actor who stays in character between performances, Tolkien pretended in his letters and private writings that he really was just a quaint British scholar dusting off old books of lore.

Tolkien was an early example of the kind of complete, obsessive immersion you find today in devotees of Second Life or World of Warcraft. I can only imagine what the stuffier dons at Oxford must have thought of this elderly chap whiling away the hours alone pretending to be a scholar of an invented world, writing philosophical treatises about it, mapping it out, trying to smooth out its inconsistencies. Certainly Tolkien’s pal C.S. Lewis never went to such extremes with his Narnia fantasies. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story about someone creating such a detailed, fantastic world — called “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” — but even that was speculative fiction.

And so there’s something both satisfying and frustrating about this posthumous collection of stories. Unfinished Tales is really just a big hunk of Tolkien fetishism. You get JRRT at his most didactic, listing chronologies of imaginary kingships as if he were tracing the lineage of Jesus. You get Christopher Tolkien at his most pompous, pointing out all of the petty differences between versions of his father’s stories in lots of dry footnotes.

All this for what? Well, for stories. Fiction. And fiction about Elves, Dwarves, and Orcs, no less. Sometimes I would finish some of the drier chapters of Unfinished Tales — say, the listings of the kings and queens of Númenor, or an account of the battles fought in the margins of LOTR by the Rohirrim — and really have to struggle to remember that this was all just part of a made-up story.

Because in the final analysis, what Tolkien’s doing with these stories isn’t scholarship or historical research. It’s pure fiction, just the same as the Flight to the Ford or the Council of Elrond or the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. It might feel like scholarship, but it isn’t really. Tolkien’s a storyteller at heart; he just tells them in a different way than anyone before him.

That leads me to the frustrating aspect of Unfinished Tales. There are lots of these seemingly endless endnotes where Christopher Tolkien talks about the different versions of the story at hand. Did his father really intend for Ar-Adûnakhôr to be the nineteenth or twentieth king of Númenor? In the appendices of Return of the King he says one thing, in draft A he says another, in draft B he says a third thing, in a letter to a fan he wrote a fourth thing, and furthermore if you compare the dates of the drafts you find that… zzzzzz.

I mean, really, who cares? We don’t give an urn of warm troll spit about Ar-Adûnakhôr. He’s just one of the thousands of names in the margins. I felt like smacking Christopher across the face and saying, “You’re the frickin’ editor now, dude. None of this is really germane to the story your Dad was trying to tell. Nineteenth or twentieth, doesn’t matter — just pick one.”

For another example, take “The Quest of Erebor,” a behind-the-scenes look at how Gandalf came about getting involved with Thorin Oakenshield in The Hobbit. Christopher Tolkien presents multiple drafts and fragments that his father wrote on the subject, with plenty of editorial commentary and endnotes in between. The drafts really don’t differ all that much. Any half-decent editor could have stitched together a 90% complete and cohesive narrative of “The Quest of Erebor” without adding a single word of their own.

For another example, take “The Quest of Erebor,” a behind-the-scenes look at how Gandalf came about getting involved with Thorin Oakenshield in The Hobbit. Christopher Tolkien presents multiple drafts and fragments that his father wrote on the subject, with plenty of editorial commentary and endnotes in between. The drafts really don’t differ all that much. Any half-decent editor could have stitched together a 90% complete and cohesive narrative of “The Quest of Erebor” without adding a single word of their own.

As for the last 10% — why didn’t Christopher just take a co-author credit and flesh it out? We already know that Christopher found enough in the Túrin saga to put together a relatively complete Children of Húrin. Guy Gavriel Kay helped him finish The Silmarillion. Most of the tales in Unfinished Tales end with a long summary by Christopher Tolkien of how the rest of the story was supposed to go. It’s not like he was transcribing the words of Moses here — why couldn’t he just finish the ones that were close to being finished?

On further reflection, though, I can think of two words that summarize why you shouldn’t flesh out your father’s notes and outlines, and those words are “Brian Herbert.” (Read my take on the first three Dune prequels.) Besides which, Christopher had a very good justification for treating the material with the reverence of a historian: his Dad wanted it that way.

Tolkien wanted his mythology to be fragmentary and occasionally contradictory; he wanted these histories to read like summarizations of retellings of half-remembered legends. As if JRRT himself was only the latest in a long line of scholars attempting to construct a complete history of Middle Earth without access to the original source materials. I think he would be tickled to discover that his writings were being treated with the same scholarly fussiness that he himself employed.

Tolkien himself recognized the absurdity of all this, as son Christopher quotes him in the introduction to Unfinished Tales:

I am not now at all sure that the tendency to treat the whole thing as a kind of vast game is really good — certainly not for me who find that kind of thing only too fatally attractive. It is, I suppose, a tribute to the curious effect a story has, when based on very elaborate and detailed workings, of geography, chronology, and language, that so many should clamour for sheer “information,” or “lore.”

If you want to see how far Tolkien’s self-awareness goes, look at the story of “Aldarion and Erendis,” which I couldn’t help reading as autobiographical. The tale concerns a prince of Númenor who strives to reconcile his love for a woman with his obsessive love of the sea. He spends years denying one or the other — either staying home and tending to his marriage, or voyaging afar on the sea and neglecting his wife. The resulting bitterness makes a sham of his marriage and sows evil in the Númenoreans that will eventually lead to their downfall hundreds of years later. It’s one of the best chapters in the book.

Now I don’t know much about J.R.R.’s wife Edith and what their marriage was like. But I’m sure there must have been many a tense night when J.R.R. secluded himself in his study with his funny little maps and philological note cards, leaving Edith to wonder if she should have married William the tax attorney instead. I’m sure a lot of women reading this story nod their heads, thinking about their husbands who like to seclude themselves in the attic and obsess over their online gaming/model trains/fantasy baseball/Civil War recreationism/whatever. (I don’t want to be sexist or exclusionary — but isn’t this kind of fetishism generally a male thing?)

Now I don’t know much about J.R.R.’s wife Edith and what their marriage was like. But I’m sure there must have been many a tense night when J.R.R. secluded himself in his study with his funny little maps and philological note cards, leaving Edith to wonder if she should have married William the tax attorney instead. I’m sure a lot of women reading this story nod their heads, thinking about their husbands who like to seclude themselves in the attic and obsess over their online gaming/model trains/fantasy baseball/Civil War recreationism/whatever. (I don’t want to be sexist or exclusionary — but isn’t this kind of fetishism generally a male thing?)

“Aldarion and Erendis” stops somewhere in the middle, and J.R.R. left only scattered notes about where he intended to take the story, but it’s clear that things were headed for a bad turn. Aldarion’s desire for the sea and Erendis’ stubborn resentment cannot be reconciled. Tolkien always works in dichotomies — good vs. evil, Frodo vs. Gollum, fealty vs. treachery, etc. — and one could argue that the main “theme” of his work is how we make our way through the world by steering between these moral pylons. I wonder if Tolkien found this particular story too painful to finish.

Aside from “Aldarion and Erendis,” the Túrin fragments, and “The Quest for Erebor,” the other major treats of Unfinished Tales include:

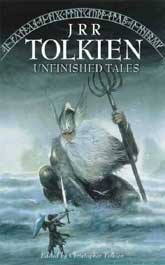

- “Of Tuor and His Coming to Gondolin,” which contains a breathtaking scene of Ulmo, the lord of waters, appearing before a mortal Man (see the third book cover on this page), as well as a fantastic description of the hidden city of Gondolin

- “The Drúedain,” an essay about those jungle pygmy dudes that help Théoden’s army get to Minas Tirith in Return of the King, and including a short story, “The Faithful Stone”

- “The Istari,” an essay on the Order of Wizards that included Gandalf and Saruman, including some tantalizing information about Alatar and Pallando, the two “Blue Wizards”

- “The History of Galadriel and Celeborn,” which offers many of Tolkien’s musings on the First Couple of Lórien, including much speculation about Galadriel’s ban from returning into the West

If you haven’t gone much beyond Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films — if you couldn’t get through The Silmarillion — if you didn’t look longingly at the maps of Middle Earth in those volumes and hunger to know what was in those blank spaces — then don’t bother with Unfinished Tales. You’re the kind of person who’s probably never bought the Special Extended Limited Edition DVD version of a film specifically so you can listen to the Visual Effects Supervisor’s commentary, which wasn’t on the original DVD, which you also own. And this is okay. You’re what we call “normal.”

But if you think you just might have a touch of the obsessive fanboy in you, give Unfinished Tales a whirl. I think Unfinished Tales is about as geeky-obsessive as I get. I have no desire to slog through all twelve volumes of Christopher Tolkien’s “History of Middle Earth” series. Though I might just breeze through The Tolkien Reader if I feel up to it. And maybe Roverandom. And maybe Smith of Wooton Major…