I’ll admit that I’m fairly new to the science fiction con circuit, but having been to Readercon twice now, I have no hesitation crowning it my favorite. The panels are generally high-minded and intellectually stimulating; the guest list is always first-rate; and best of all, there isn’t a single dork with a Klingon outfit or a lightsaber to be found.

Of course, the flip side is that once the bar closes at 12:30 pm, there’s pretty much nothing to do but go back to your room and sleep. Peter Watts, Jenny Rappaport, and I tried to find a party after last call on Saturday, only to get accosted by a very angry woman asking “us people” to keep the noise down. When we did find the one open party in the hotel, security arrived two minutes later to shut it down.

Highlights of my weekend include:

- Getting to ogle Mary Robinette Kowal‘s steampunk laptop (as recently featured on Boing Boing) and listening to plenty of stories about her beaver. And how did I thank her for being one of the coolest people on Earth? By going into an unstoppable coughing fit during her panel on techniques for reading aloud and having to duck out of the room.

Sharing many a beer, many a story, and many a laugh with George Mann and Christian Dunn of Solaris Books. The fact that George and Christian accepted my SF short story “Mathralon” for publication in their forthcoming second Solaris Anthology of Science Fiction helped my mood quite a bit too. I introduced George and Christian to Mary Robinette Kowal, which may have been a mistake, because the rest of the con they kept making obscure comments about clockwork monkeys.

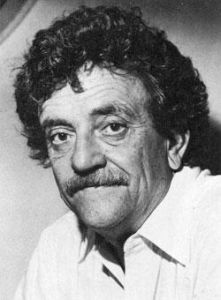

Sharing many a beer, many a story, and many a laugh with George Mann and Christian Dunn of Solaris Books. The fact that George and Christian accepted my SF short story “Mathralon” for publication in their forthcoming second Solaris Anthology of Science Fiction helped my mood quite a bit too. I introduced George and Christian to Mary Robinette Kowal, which may have been a mistake, because the rest of the con they kept making obscure comments about clockwork monkeys.- Continuing to confound the world by appearing at the same con with Scott Edelman (see photo to the right) and insisting that we’re not related.

- Sharing a panel on alternative points-of-view in fiction with (among others) Peter Watts (of Blindsight fame) and gossiping about the biz with him and Jenny Rappaport over beers until closing time. Turns out Peter is just a fabulously nice guy with a very wry sense of humor and a big ol’ Canadian accent.

- Gabbing over meals and beers with Matthew Jarpe, author of the David Hartwell-edited debut novel Radio Freefall, and listening to his humorous reading from same.

- Breakfasting with the divine Elizabeth Bear not once, but twice. I will even forgive her for accidentally calling me “Scott” during one conversation.

- Discussing J.R.R. Tolkien and George R.R. Martin, among other things, with Realms of Fantasy slushmaster and all-around nice guy Doug Cohen.

- Watching fellow Pyr author Kay Kenyon promote the hell out of her new novel, Bright of the Sky, through readings, panels, talks, fliers, signings, ads, and who knows what else. I also got a chance to share drinks and a ride back to Logan Airport with Kay and fellow Seattle-area author Louise Marley.

But the folks wandering the halls seemed to lean heavily towards the SF fanboy (and fangirl) sphere. You had the Chubby Guy Who Dresses Like a Character from Tron (pictured to the right), the Chubby Guy Who Dresses Like Zorro, the Chubby Guy Who Filks Like a Zen Master, the Not-at-All-Chubby Guy Who Dresses Like a Jedi, and the Attack of the Thousand Chubby Women Showing Enormous (And Occasionally Inappropriate) Amounts of Cleavage. As for the technogeeks, occasionally you’d see some scrawny, bespectacled soul with a Linux advocacy t-shirt huddled over his laptop in the corner.

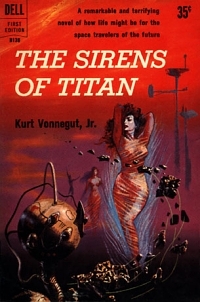

But the folks wandering the halls seemed to lean heavily towards the SF fanboy (and fangirl) sphere. You had the Chubby Guy Who Dresses Like a Character from Tron (pictured to the right), the Chubby Guy Who Dresses Like Zorro, the Chubby Guy Who Filks Like a Zen Master, the Not-at-All-Chubby Guy Who Dresses Like a Jedi, and the Attack of the Thousand Chubby Women Showing Enormous (And Occasionally Inappropriate) Amounts of Cleavage. As for the technogeeks, occasionally you’d see some scrawny, bespectacled soul with a Linux advocacy t-shirt huddled over his laptop in the corner. The Sirens of Titan (1959) — 4 1/2 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A)

The Sirens of Titan (1959) — 4 1/2 stars (Vonnegut’s own grade: A) My first exposure to Vonnegut was through his seminal collection of short stories, Welcome to the Monkey House. I was probably around 13 or 14. Up to that point, my reading had consisted mostly of straightforward, unironic science fiction and fantasy: J.R.R. Tolkien, Piers Anthony, Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov. My other recent obsession at that time was Douglas Adams, who strove all his life to achieve Vonnegutdom with mixed (albeit funnier) results.

My first exposure to Vonnegut was through his seminal collection of short stories, Welcome to the Monkey House. I was probably around 13 or 14. Up to that point, my reading had consisted mostly of straightforward, unironic science fiction and fantasy: J.R.R. Tolkien, Piers Anthony, Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov. My other recent obsession at that time was Douglas Adams, who strove all his life to achieve Vonnegutdom with mixed (albeit funnier) results.